|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| AUTOCAR w/e

22/2.9 June 1974

LONG TERM REPORT 36,000 miles By Chris Goffey IMPRESSIVE BUT EXPENSIVE |

|

||||||||||||||

|

I then took over the car and sent it for the 27,000-mile service. This time CitroŽn looked at the adjustment of the headlamps, which I had thought were too high, at all the door catches which were allowing doors to rattle and an infuriating whistle to develop from the front seals, a side lamp cover had to be replaced, and the brake lamps had started jamming on. We also asked for a new silencer to be fitted and for a “clunk” in the rear suspension to be investigated. They spent 9.67 hours on the car and the total cost of the service, including £16.37 for a new silencer, came to £55.64. This introduction to the servicing costs of the car rather tended to colour my impressions from then on. I used the GS for commuting from my Buckinghamshire home, 27 miles down the M4 and the Cromwell Road to our Blackfriars offices every day, and for long-distance high-speed business and touring, trips to various corners of England and Wales. I took the car over at 27,000 miles, and was at once impressed during my commuting driving by the ride comfort and roadholding. The paintwork was showing signs of the mileage and the long exposure to London’s traffic and commercial pollutants in the atmosphere. There were traces of rust here and there on the body. The reflectors inside the huge headlamps had started to corrode quite badly however, at their leading edges. I had been warned about the difficulties of starting the engine on cold mornings. Several times I saved myself from a long wet walk to the station only by pushing the car down the hill I live on, and then jumping in. This procedure was too energetic to become very popular with either myself or my wife, and I soon picked up a technique of using full choke and pumping on the throttle pedal to get the car going. If you could catch it on the first cough during the initial spin of the starter you were home and dry -with an immense cloud of blue smoke which often blotted out the lane, the car started. If you missed that first cough and let the engine die, you were in trouble. We never actually discovered what CitroŽn did to the car to cure this trouble. We had tried plug changes and carburettor adjustments without a great deal of success. But during a routine service I had once again complained and the car had returned with a clean crankcase and signs that the heads had been off. We were not told exactly what had been done, but at shop floor level I was told unofficially that very early cars such as ours used to suffer from wear in camshaft and cam followers, resulting in the valves not opening as much as they ought to, thus affecting performance and cold starting. Be that as it may, the car returned from the 30,000-mile service transformed. It accelerated without the spluttering and hesitation I had begun to notice before, and it started on the first turn of the key, cold, wet, misty or fine. Soon after the start of my term of ownership I took the car to Wales and thence up to the Lake District. Just before I was due to leave, the brake warning light started to glow, and I dashed over to Slough on the morning of my departure to have a new set of front pads installed. The pads had lasted 5,300 miles, the normal sort of pad life we had become used to. I set off` and reached Wales with no problems - and then had to endure intermittent and infuriating misfiring for the rest of the week. Cruising at around 70 mph, the car would suddenly falter and then cut-out completely, coasting down to around 15 mph before suddenly spluttering into life again and picking up. Obviously an ignition component was loose or was breaking down, but despite repeated stops and pulling and pushing every connection in sight I could not cure the trouble. I pulled into the CitroŽn service agent in the Lake District to see if he could help. The service manager indicated a car park full of CitroŽns waiting for service and shrugged – “Bring it back in 10 days or so,” he said. I was due to return to London two days later. While the car was behaving, (the breakdowns came only during the long high-speed journeys) I took it right up into the mountains, along rough tracks and sheep paths. With the suspension control lever in the middle slot between jacking and normal, the car lifted itself on its hydropneumatics and clambered over all sorts of obstacles with amazing ease. Even with the suspension raised, ride comfort was unaffected, and I was able to drive at 30 mph across rough going. With a bit of snow on the Peaks, the roads were slippery at times, and I had my first opportunity to try the stability and traction on this sort of going. I like a car to break away at the back under power on slippery surfaces, and I can_then hold it on opposite lock and feel my way around. Driving the CitroŽn at speed on such going was a very different, and at first unnerving, experience. The car stays neutral, breaking away neither at front or rear up to very high cornering limits. But beyond a certain point things start to happen fast and you need to keep your wits about you, since by then you are going so much more quickly than you would be in a conventional car. Powering through a slippery corner, the front end tends to carry straight on with the wheels locked over, but lifting one’s foot or even dabbing the brakes kills the understeer and the car lurches back on to the chosen line. Braking hard on slippery surfaces produces the same ploughing-on, again, lifting off the brake pedal brings the car back on to line. In no circumstances will the back of the car come unstuck, even during the most extreme manoeuvres. Roll angles can become quite high, but dive and squat are always eliminated by the suspension, and the car remains incredibly agile. Despite a rather low steering ratio, the “swervability” of the GS is unmatched by other cars in its class. The car is no ball of fire however, the later 1220 demonstrating how the roadholding is well in excess of the available performance. The little 1,015 c.c. engine feels overstretched much of the time, and while the car cruises comfortably at 80-85 on Continental motorways, the revcounter needle is well past the 5,500 rpm mark at this speed. In fact I have held the little engine at the red line for hour after hour without apparent ill-effect. But the fuel consumption is by no means good for a car with an engine of this size. It holds its own in London traffic, and despite a rather slow 0-60 time, the fitting of a rev counter and the ability of the little engine to rev smoothly round to 7,000 rpm belies the figures, and makes the car feel quite spirited. It was in the Lake District that I first discovered that it was possible to get bad brake fade. It should be emphasized that this occurred only under extreme conditions, and is probably owed to the inboard location of the front discs. Nevertheless if the brakes are being used hard on twisty roads where the speed does not climb enough to promote a great deal of cooling air to the‚ discs, fade is an ever-present problem. The car is certainly not hard on tyres. It left me at 36,000 with 4mm on the rears and 3mm on the fronts , a most creditable performance when one bears in mind the hard use the car had had when it covered the RAC Rally, for example. It would appear that in normal circumstances, 50,000 miles is not beyond the normal life of the Michelin ZX tyres. The 1220 of course has better fuel consumption, illustrating how hard the smaller, 1,098 c.c. (sic) engine has to work. It also has thicker and bigger discs giving a 50 per cent increase in swept area. On that trip back from the Lakes and Wales the car continued to misbehave, and was eventually abandoned in the office car park. CitroŽn took it away to Slough and tried to trace the fault, and discovered that the wire from the coil to the distributor had broken inside the cable before the brass terminal; it was making intermittent contact. About this time too (29,000 miles) the headlamp flasher and horn stalks became very stiff to operate. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

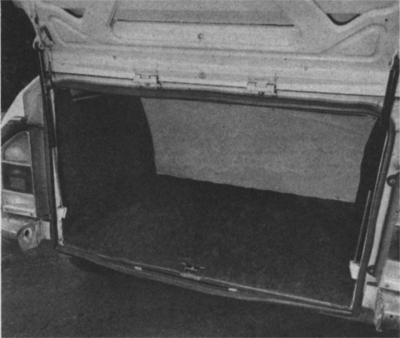

| Left inside,

the rather unpleasantly coarse carpets were a bit dirty but not badly

worn Above the CitroŽn boot is enormous and completely uncluttered. |

|||||||||||||||

| However, since you tend to stoop under the the upward opening boot lid, heavy luggage is dragged out over the lip, tearing off the rubber seal which then lets water into the back of the car in wet conditions on motorways | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| © 1974 Autocar/2011 CitroŽnŽt | |||||||||||||||