Citroën XM a

glorious failure?

|

|

|

The XM

represented a major failure for PSA. The

reasons for this are many and some of them are

less than clear. Hopefully this article will

go some way towards offering some

explanations. Before doing so, it is necessary

to place the XM within an historic

perspective.

In the beginning

Initially, Citroën

pitched his products at the bottom end of

the market - above the cyclecars that

provided basic, mass market transportation

but well below the luxury Gran Turismos

offered by the likes of Delahaye, Bugatti, Panhard, Hispano

Suiza, Bentley, Rolls Royce et al. In the

aftermath of World War One, motor car

manufacture was a labour intensive,

artisanal affair and the products were

expensive. Although there were large numbers

of manufacturers, thanks to fiscal tariffs,

it was not economic to sell one's products

abroad.

André Citroën was a

great admirer of Henry Ford and sought to

emulate his success in Europe by employing

mass production techniques. This enabled him

to offer more car for the money and charge

less money for the car. However, unlike Ford

which offered but one model with but one

colour (any colour you like as long as it is

black), Citroën offered a range of cars with

a multitude of different body styles (and a

bewildering range of colours!). This

philosophy stood Citroën in good stead as

his firm produced a range of dull but worthy

cars at prices few of his competitors could

match.

|

|

C6 – the original

haut de gamme

Ever ambitious and ever

willing to exploit a niche, Citroën saw the

need for a competitively priced, high

performance, luxury car which would both

spearhead an advance into the upper echelons

of the market and would also act as an

aspirational product whose kudos would

reflect on cars lower in the range.

The result, in 1928 was

the haut de gamme (top of the range)

AC6

(or C6), equipped with a 6 cylinder

engine and every conceivable extra, it

offered most of the refinement of a Gran

Turismo at a fraction of the

price.

Its 1932 successor, the

15,

built on these strengths but it was, in

truth, little more than a copy of

contemporary American cars.

|

|

|

|

The 22CV and

the 15CV

In 1934, with

the launch of the 7CV

Traction, Citroën no longer

had an haut de gamme model.

However, it was the intention of the

company to offer an entire range of

cars all based on the Traction and

at the top of the range would be the

V8

22CV. For well documented

reasons, the 22CV was never launched

and the position of haut de

gamme fell to the six cylinder

15

Six. The 15 was so far ahead

of its competition that the company

made very few modifications to it

before it was replaced in 1956 by

the DS19.

|

|

|

|

In the austere

years after World War Two, the

French luxury car makers disappeared

– with the exception of Panhard

who were reduced to making

economical, small cars.

Thus there was

little competition for the 15CV –

its Renault,

Peugeot

and Ford

peers were smaller and did not offer

the same levels of comfort or road

behaviour, even if they were more

"modern" in their styling.

|

|

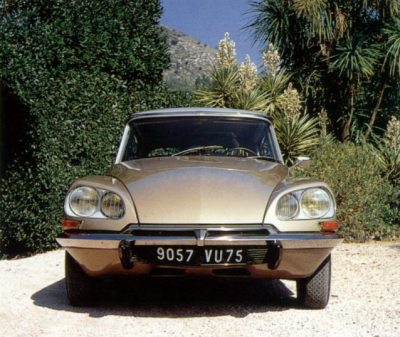

The

DS

The DS offered the kind of

hedonistic comfort that

few other manufacturers

could approach. Not only

did it offer unrivalled

sybaritic luxury but it

managed to do so in a

package that was both

stunningly beautiful and

technologically advanced.

If it suffered major

problems in its early

years, this did not damage

its reputation too

severely - if anything it

added to the mystique. And

the clientele in those

days was less

sophisticated as far as

expectations regarding

reliability are concerned.

|

|

|

|

As if the standard DS were not

luxurious enough, three new models

were launched. The Prestige offered

limousine style accommodation in the

rear although the chauffeur,

thankfully separated by a glass

screen from the bloated plutocrats

in the rear, endured IDesque

seating… And then there was the

Pallas for the person who did not

want to give up the driving seat to

a hired hand but still demanded the

luxury of the Prestige. But the haut

de gamme undoubtedly was the Décapotable built

by Henri Chapron. Those with more

money than taste could flaunt their

extravagance with one of the bespoke

Chapron creations.

|

|

For a few short

years, Facel

Metallon hand built cars in

the pre War Gran Turismo

fashion but sales of these were

minuscule in comparison to those of

Citroën and when the company

disappeared in the mid sixties,

Citroën was free to besport itself

without any domestic competition.

The foreign competition ? Mercedes,

Jaguar, Rover, etc. suffered from

high prices as a result of import

taxes and the DS reigned supreme. In

the France of the early sixties, if

you wanted a top of the range luxury

car at a sensible price, the choice

was between a DS, a DS Prestige or a

Chapron DS of one type or another.

If the DS suffered from shortcomings

in the engine department, this was

more than made up by its strengths

in other areas. Over the years, the

DS was refined and improved. More

powerful engines made up the

shortfall in straight-line

performance and a couple of

restyling exercises ensured that it

still looked contemporary.

|

|

|

The SM

The SM

was intended to be positioned above

the DS in the model hierarchy and,

had events not conspired against it,

might very well, in four-door guise,

have supplanted the DS. The SM was

designed to accommodate the four

cylinder powerplant from the DS as

well as the Maserati V6. Sadly,

escalating oil prices coupled with

the widespread imposition of speed

limits and the company's parlous

financial state killed the SM and

the DS laboured on until 1975.

|

|

The CX

At launch, most

D owners viewed the CX

as a retrograde step. Available only

with the DS20 engine, with a manual

4 speed transmission, with reduced

interior room and a fairly basic

trim level, without the steerable

lights of the D, the only obvious

advance was the fitting of DIRAVI

steering on some models.

Had the company

had more resources, the CX range

would have included long wheelbase

variants (subsequently introduced

with the Prestige and Limousine), a

Trirotor Wankel

and a V6 Maserati.

The ultimate

luxury vehicle would have been the

Maserati Quattroporte (below) -

equipped with hydropneumatic

suspension, fully powered brakes and

DIRAVI, this car was pure Citroën

apart from the engine and styling.

|

|

|

With the gradual

fall of fiscal barriers within the

EEC, cars began to sell outside

their country of origin and the CX

faced competition in all its

markets, including France.

The CX was

rapidly developed to face up to the

likes of Mercedes, BMW, Jaguar,

Rover, Ford, BMC, Vauxhall and Opel.

Bigger engines, CMatic semi-

automatic transmission (and later

fully automatic transmission),

Pallas and Prestige trim all

followed in fairly short order and

helped maintain Citroën’s reputation

as the "anti-Mercedes" but the

Germans were fighting back.

|

|

By the early

eighties, the CX was beginning to

look somewhat dated; the science of

aerodynamics had moved on (the Audi

100 in particular showing the way

with a CD of 0,30 compared with the

0,36 of the CX) and competitors were

offering cars that did most of what

the CX did without the attendant

complications (be they real or

imaginary). Furthermore, the Germans

were ahead of Citroën in the field

of safety – ABS was introduced by

Mercedes in 1979 and by Ford in 1985

as a standard fitting in the

Scorpio. It was only following

widespread criticism of the

inadequate brakes of the CX GTi

Turbo that Citroën offered ABS as a

costly option. And where the CX

Automatique had a three speed box,

the competition offered four speeds.

From being at the forefront of

technical innovation and active and

passive safety, Citroën was obliged

to play second fiddle to the

Germans.

PSA had decided

to concentrate its resources on the

new, mainstream car that would make

or break Citroën – the BX.

Where the BX employed the very

latest, lightweight TU range of

engines, the CX laboured on with the

Sainturat-based engines from the D

or the harsh and unrefined PRV

engine found in the Reflex and

Athena. The diesel engines used in

the CX were basically dieselised

versions of the D lump and were less

refined than the XUD engines fitted

to the BX. Had the money been

available, the CX restyle would have

been much more than the fitting of

new bumpers and interior – the

underpan would have been cleaned up,

the roof gutters would have

disappeared, a flush fitting screen

would have been fitted, the roof

line would have been raised to

provide improved rear headroom and a

hatchback would have been fitted.

Extensive use of plastics per the BX

would have helped reduce weight but

PSA said no.

The CX was under

threat, not just from the Germans

but also from the Renault 25 and its

stablemates, the Peugeot 604 and top

of the range BXs.

Not the CX

replacement

But let us

backtrack to 1980. Some five years

after Robert

Opron had left Citroën, the

Bureau d'Etudes, under the direction

of Jean Giret, turned from the soon

to be launched BX and concentrated

its energies on working on a

replacement for the CX. This task

was undertaken without the knowledge

or approval of Xavier Karcher and

therefore without any formal design

brief although those in the know

referred to it as Projet

E. The basis on which Giret's

team operated was a re-dimensioned

CX and the car was fitted with a two

piece tailgate allowing a classic

boot or hatchback configuration as

desired. Frontal treatment was not

dissimilar to that of the BX.

Peugeot had made it clear to Citroën

that the CX was to be the last

"quirky" Citroën. When Art Blakeslee

discovered this model, he ordered it

to be destroyed - and PSA then

imposed its personnel in the Bureau

at Vélizy. This meant that any

successor to the CX was going to be

a far more conventional beast and

would make extensive use of

components shared with other

vehicles in PSA’s range.

The DX?

In late 1984,

PSA's Management Board asked three

styling centres to submit their

proposals for the CX replacement -

two of the centres were in-house PSA

(Vélizy and Carrières-sous-Poissy)

and the third was Bertone. Marcello

Gandini, designer of the BX while at

Bertone also submitted a pair of

models. The design of Projet

V even at this early stage

required a floorpan that would be

shared with Peugeot’s new flagship

and with the Saab 9000. The decision

was taken to employ the pseudo

MacPherson strut front suspension of

the BX and the XU range of engines.

For the first time since the demise

of the SM, a V6 would also be

offered.

Eventually,

Bertone’s design was accepted but

the production version lost the

semi-enclosed rear wheels and smooth

flanks that were part of the

original proposal. Also rejected

were head-up instrument displays and

a six headlamp set up.

In 1998, Citroën

showed the Activa

prototype at the Paris Salon.

Activa was fitted with active

suspension and four wheel

steer and it was thought inevitable

that the DX (as the pundits had

named the CX replacement) would

feature this technology. In the

event, a simplified version of

Activa’s suspension was fitted and

passive rear steer, originally

introduced on the ZX was not fitted

until the mid 90s.

Bienvenue à

la XM

On 23rd

May 1989, the new car went on sale.

Christened XM in order to pay homage

to the SM which was the last six

cylinder Citroën, it also featured a

kicked up waist line that was

reminiscent of the SM. Originally

available with a choice of a

carburettor XU engine bored out to 2

litres, a fuel injected version of

the same or a V6, the considerable

extra weight of the XM compared with

the BX endowed the 2 litre versions

with pedestrian performance and even

the V6 was slower than the BX 16

Soupapes. In July 1990, a 170

bhp 24 valve V6 was offered.

Virtually all the 176 24 valve cars

developed problems with oil flow

which led to premature camshaft

failure. Citroën must have been

aware that this engine was stretched

beyond its limits but this did not

dissuade them from manufacturing

such a severely flawed car. Then in

1993, a turbocharged 2 litre XU

engine was provided which finally

overcame the performance deficit of

earlier 2 litre models.

The diesel

versions similarly suffered from

lack of performance – the XUD was

extended to 2,1 litres and offered

110 bhp compared with the 120 bhp of

the CX 25 Turbo D which was a

lighter vehicle than the XM.

Contrast this however with the 143

bhp of the Mercedes 300D. The

success of the BMW 325TDs led PSA to

drop the 4 cylinder 2,5 litre engine

from the C25 van into the XM in

1996. This unit was, at 130 bhp,

powerful but it could also be

thirsty. Having only four cylinders

as opposed to the six cylinder units

that powered the Germans which were

sold at similar prices and lacking

the image of either BMW or Mercedes,

its appeal was limited to a small

circle of Citroën enthusiasts who,

in Britain at least, mainly

purchased second-hand vehicles since

the majority of them were

pre-registered by Citroën dealers.

Following the

restyle of 1995 and the fitting of

Hydractive 2 which had been

pioneered in the Xantia,

the XM was not really developed any

further. Activa suspension was not

fitted to this haut de gamme model

but to the mainstream Xantia. The

same held true for the new V6

jointly developed by PSA and Renault

which first saw the light of day in

1996 in the Xantia and a year later

in the XM and also for the

auto-adaptive gearbox. The headlamps

which had been a source of much

criticism were revamped in 1996 but

right hand drive cars continued to

be fitted with the original,

inadequate units – presumably the

sales figures did not justify the

development of RHD versions. Similar

lamps were fitted to early versions

of the Xantia but sales were

sufficiently healthy here in Britain

to justify developing replacements.

Other mainstream

manufacturers had abandoned the

large car field to the Germans –

Fiat threw in the sponge in 1995 and

Ford did likewise in 1997. Apart

from the Germans, the only other

players are Saab, Volvo and GM with

only GM being a volume manufacturer.

In 1989, 46,282

XMs were sold worldwide. In 1990, a

total of 96,196 were sold and

thereafter, numbers declined rapidly

- 49,119 in 1991, 43,487 in 1992,

20,977 in 1993, 20,591 in 1994,

17,799 in 1995, 12,500 in 1996,

9,594 in 1997, 7,500 in 1998 and

only a couple of thousand in 1999.

More than 45% of total XM production

occurred in the first two years of

an eleven-year run. From 1996, in

its home market of France, the XM

was outsold three to one by each of

its German competitors. Production

ended without any sort of fanfare in

June 2000.

|

|

Year

|

Worldwide

|

UK

|

UK

Sales as a percentage

of world sales

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2,49%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Approximately

ten per cent of all XM production

went to the Netherlands where the

car continues to be very popular

with customers and where values hold

up well. Contrary

to the position in Britain,

most specialist Citroën dealers

would be happy to have ten low

mileage, late model XMs sitting on

their forecourts since they have

waiting lists. Many former DS and CX

specialists are now turning to the

XM as their clients have learned to

recognise its very real qualities.

In the French

Contrôle Technique (MOT) statistics,

the XM came out as the third most

reliable luxury car – after the

Mercedes 190 and BMW 5 series. In

the 1998 EuroNCAP safety tests, the

XM was reckoned to be one of the

safest cars in its class – not bad

for such an old design.

At launch, PSA

said that 4 x 4 versions of the XM

would follow, together with a classic three

box design intended primarily for

North America.

The XM fell

between two stools – it was not

different enough to attract the

hardened Citroën enthusiast but was

too different to appeal to

mainstream purchasers. In efforts to

attract mainstream purchasers, the

feel of the brake pedal was made

more conventional thanks to the

insertion of a deformable tube in

the brake valve to make the pedal

feel spongey. DIRAVI was only fitted

to left hand drive V6 models and was

quietly dropped in 1997. The DIRAVI

equipped cars actually had lower

geared steering than the lesser XMs.

The non-turbocharged XM 2 litre was

slower and substantially thirstier

than the BX19TRi and furthermore,

thanks to its Hydractive suspension

did not ride as well.

In some

respects, the XM continued in the

traditional Citroën mould – it was

released prematurely – by at least

eighteen months – and suffered from

considerable teething problems which

gave it a reputation from which it

never recovered. The use of totally

inadequate wiring and connectors was

a recipe for disaster and was

undoubtedly brought about by the PSA

bean counters’ desires to reduce

costs wherever possible. Quality

control was not all that it might be

– many cars suffered from water

leaks and an appetite for front

tyres and brakes did not help

either.

And here in

Britain, the majority of dealers

hated it. They hated it because it

was a slow seller and because of its

reputation for unreliability. The

result was £10k depreciation in the

first year. And for the hapless

owner of one of these cars, there

was the hostility and ignorance of

the dealer network to add to your

woes. To an extent, the hostility

was understandable – why tie up

capital in a vehicle that might sit

in your showroom for six months when

you could shift a dozen Xantias in

the same period? The ignorance is a

direct result of the hostility – few

dealers ever got to work on an XM so

it was terra incognita to

them. Diagnosing intermittent

suspension faults cost the dealer

man-hours that could not easily be

passed on to the customer.

And then there

is the appearance - a car that looks

like a hatchback in a market that

eschews them as utilitarian.

Unusually styled cars do not

normally sell well in this area of

the marketplace. Nor do front wheel

drive cars.

Yes, the XM was

undoubtedly a failure in commercial

terms and yet it offers all of the

traditional big Citroën strengths

and virtues; the ability to make

light work of long journeys in

adverse conditions, unique styling,

excellent aerodynamic performance,

good economy (V6 aside), superb

comfort and luxury; the list goes

on. It offers a unique driving

experience and in true Citroën

style, looks like nothing else on

the road.

When it was

launched, I observed that it looked

as if it had been designed by a

committee that had never met.

Familiarity has led me to modify my

views – I think it is a great design

which is let down by detailing. The

concave flanks do little for the

aesthetics and the leading edge of

the bonnet should be continued to

the line above the headlamps. There

are too many panes of glass in the

much-vaunted "band of light" while

the front quarter lights are so

designed that when it is raining,

the exterior mirrors are worse than

useless thanks to the water running

across these panes. I like the

exterior door handle design but some

people have likened these to RSJs.

It is a pity that the rear wheels

are fully exposed. The design has

not dated because it is essentially

right – just like the DS and the CX.

I suspect that C5

will look old-fashioned in 2012.

CAR magazine’s

acerbic comment was "It will be a

great car when it is finished".

Unfortunately, it was both never

finished and is now finished. It was

never finished since development

ceased. It is finished because

production has ceased.

The future

The XM came to

the end of its life without any

immediate successor. For the last

half of 2000, the haut de gamme

was the V6 Xantia. The C5

replaces the Xantia,

not the XM (although it does

encroach on the XM's territory). C6 will

appear, eventually, but for at least

18 months the flagship will be the

V6 C5 – just a large-engined version

of a mainstream Mondeo competitor.

C6 is so different looking from its

current competitors (with the

exception of the new Renault) that

it too may suffer from the

conservatism of buyers. On the other

hand, it may be that the market is

changing; people may be becoming

bored with driving ubiquitous BMWs

and Mercedes. And all this

presupposes that C6 will be reliable

from day one, that it will offer a

unique driving experience. Certainly

Audi has demonstrated that cutting

edge technology can be a powerful

force in attracting customers,

indeed Audi seems to have wrested

the technocrown from Citroën – it is

time to snatch it back.

Working on the

premise that one should learn from

one’s mistakes, I gain the

impression that Peugeot-Citroën’s

attitude is "We can repeat them

without any difficulty" since once

again, the marque will have two

flagships competing with one

another.

My thanks are

due to Paul Johnson, Wouter Jansen

of CITROExpert

and Citroën

UK Ltd. for their invaluable

input into this article. The idea

for this article came about as a

result of discussions with Nigel

Wild of the Citroën

Car Club who cautioned me

against suggesting that the XM is a

"real Citroën" since, like its

forebears, it was launched while

still in prototype form. As you will

have read, I ignored his warnings

since I believe the point is valid.

Furthermore, the word is out that a

number of C5s issued to dealers have

suffered from teething problems –

failed power steering – over-light

power steering – braking problems –

rear suspension sub frame problems -

problems with some of the

electronics - lack of power in the

2,2HDi. If this is true, then C5

continues in the grande

tradition. I rest my case,

Nigel.

©

2001 Julian Marsh

|

|

|

|